It’s difficult to comprehend the scale of Severin Zotter’s accomplishment in winning the Race Across America at his first attempt.

The numbers - a journey of 3,020 miles, east to west, across 12 states, in eight days, eight hours and 17 minutes - barely do justice to his achievement.

Instead, it is the details that emerge in a conversation with a man who, until recently, worked as a support worker to addicts in his home town of Graz, and is now a full-time father to baby Jonathan, that provide real insight.

An example? Zotter reveals, with no greater emphasis than one might place on declaring a preference for tea over coffee, that, “for me, a bike race really starts after 24 hours.”

Endura could hope for no greater endorsement of its 700-series pad. Zotter wore it in the Pro SL Bibshort for the victory that might come to define his career. It has been retained for the new Pro SL Bibshort II. If it ain't broke...

“It was perfect,” Zotter maintains. Honestly? We make like the pad and try to take off the pressure. He’s not obliged to be complementary.

“I mean, I had some problems with my ass; like, after riding for two days, I had some points where the skin had opened, but we changed the saddle, and at the end of the race, after more than eight days, I had perfect skin, so the shorts did a really good job.

“There are so many things you have to organise before the race, and you have to check what you need to give a good performance, or even just to finish the race. The Endura shorts were an ideal opportunity for me to do a good race. I was really happy that I got them.”

Flattery gets you everywhere, but we’re not fishing for complements. While it’s nice to hear that the Pro SL Bibshort performed well (and we’re confident that the Pro SL Bibshort II is better still), the most astonishing parts of Sevi’s Race Across America do not concern clothing.

Tales of a three-minute nap, taken after an opening stint of some 745 kilometres, or of plunging his head into a freezing pool of water to shake off the 35-degree heat of the Arizona desert are of greater interest - even to us.

POOL SIDE

A mirage is a cruel illusion, often suffered by those who find themselves thirsty and desperate in desert conditions. Zotter, riding into Congress, Arizona on the second day of his Race Across America, and perhaps still considering the wisdom of sleeping for only three minutes at the end of day one, might have been forgiven for dismissing the vision of a waiting pool as a mental trick.

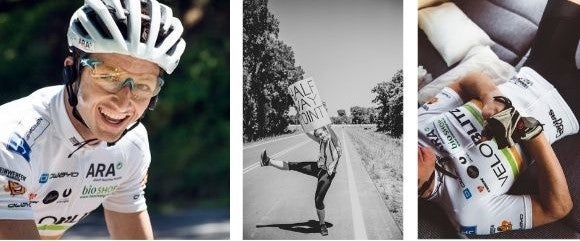

Happily, the volunteers who staff Timing Station Six make sure that their inflatable pools not only are shielded from the sun by lightweight canopies, but are large enough for the rider to immerse himself completely. Zotter, however, had no time for bathing. A dip of the head, captured in the striking image that opens this article, had to suffice.

“I didn’t jump in, because I didn’t want to lose too much time, but still, I couldn’t just pass it,” he says. “To put your head in the water and cool down is as good as it gets. It was a great moment. I stopped for two minutes, I think, getting rid of the jersey, getting some water on board, eating some water melon, and then on we went.”

He pauses. “That was it, actually.”

So blunt a description of such a dramatic image is pure Zotter. Good natured, modest to a fault, ready to chuckle at a level of dedication approaching mania, the Austrian has many qualities, but a tendency to melodrama seems not to be among them.

ARGUMENTS WITH THE BODY

How deep is the pain a rider experiences when racing for eight days, across 12 states, with a total ascent of 175,000ft?

Zotter admits that RAAM was a race he was afraid of - a startling admission from a man who warmed up with ultra-distance events around Austria, Slovenia and Switzerland, including his home event, the Glocknerman, as savage a 1,000km parcours as might be imagined, crowned with a double ascent of the towering Großglockner.

His attitude to pain management is revealing. Perhaps there is something of the social worker in Zotter’s conciliatory approach.

“I had something like an agreement with my body. I said, ‘Ok. When the pain is coming, you tell me. I will try to do everything I can to relive it, but in the end, I have to go on.’”

The pain was not limited to his legs. In the final 300km, Zotter had difficulty lifting his head, despite extensive pre-race work on his neck muscles. The condition is not unknown among RAAM participants, especially those who ride in the time-trial position (Zotter used a TT bike and a standard road bike).

“In the races before, I tried to do something similar, but this was like absolute acceptance of what was happening…I don’t know exactly the right word in English, but something like total confidence in my team and in my ability to finish the race.”

He searches for the correct English phrase.

“Trust? Faith? Maybe - I don’t know exactly the right word - but those two things. Faith to finish the race, and acceptance that the pain was coming.”

NO PRO

If Zotter’s mantra of “total acceptance” of pain and making agreements with his own body makes “Shut up, legs” sound passé, it’s important to note that his métier is different to that of the WorldTour professional.

Zotter says it was never his ambition to ride the Tour de France. He discovered cycling as a comparative latecomer to the sport, when he worked as a courier in Graz. The day job led him to alley cat races among his colleagues, and later against the messengers of Dublin during a year-long study break in Ireland.

On his return to Graz, Zotter joined the “sportier” couriers in 24-hour team races, and later competed in 24-hour solo events. Teaming up with an old school chum, who had pledged as a 15-year-old one day to tackle the Race Across America, our hero gained an insider’s view of the race by serving as a member his friend’s support crew.

“I had a really good idea what the race was about because I had to follow him the whole way,’ Zotter explains. “I had the night shift and had to talk with him and bring him through all the difficult times. I was kind of fascinated by the race, and a bit afraid, and that’s how I came into long-distance cycling.”

In a branch of the sport now commonly described as ultra-distance - one that offers a cruel mix of unrelenting pain and the time to reflect upon it - a late start is no disadvantage. If the young bucks of the WorldTour depend heavily on their youth for success, then the greater psychological challenge presented by racing much greater distances plays to those with greater life experience. There is a physiological aspect too, of course, and a man hits the sweet spot on the speed-endurance axis in his thirties and forties.

Do not run away with the idea however that ultra-distance events are rambles. There is a reason that RAAM is defined as the Race Across America and not the Ride Across America. Zotter, who took an early lead that he did not relinquish, admits to some disorientation.

“It’s a bike race, but after the first 100km, I had only seen another cyclist twice on the road, so it was pretty difficult, especially on the seventh and eighth nights, to stay focussed and to recognise that you are in a bike race, especially when you’re cycling on your own, somewhere in the middle of nowhere. Just to know what you’re doing and to still push hard can be difficult.”

TO SLEEP, PERCHANCE TO DREAM...

“I did about 745km in the first 24 hours, and then I had a three-minute power nap, not because I really needed it, but because the team had said: ‘Let’s start with the power naps earlier. Maybe a shorter sleep at the beginning of the race will give you more energy at the end.’”

Zotter’s ratio of resting to riding is revealing. He raced for 8 hours, 8 days, and 17 minutes, during which time he slept for a total of just 8 hours and two minutes. He drills down to still greater detail: six sleeps of between 55 minutes and 1hr and 15mins, and 10 power naps, each about 10 minutes long.

This was even less than he had planned for. Zotter missed two of the scheduled ‘longer’ breaks. The first night we have discussed (a three-minute nap to recover from an opening salvo of 745km), and on the third night, he was at altitude.

“We were in the Rockies, at more than 2,300m [altitude]. It wasn’t my decision, but my team told me not to take a long sleeping break, because up there it’s not good for recovery, and you can get lung problems. They said: ‘Sevi, you’re going to get 10 minutes tonight, and then you go on.’”

The strategy worked. The longest sleep of his entire effort was just 75 minutes. His doctor promised to wake him each time before he reached the deep sleep phase, and proved as good as his word.

“I think he did pretty well,” Zotter reflects. “It took them seven minutes to dress me, and focus me on the bike again, and I was more or less orientated every time. Just once, I wasn’t, and it wasn’t nice. We had a problem with our van, and I had to take the longer sleep break in the follow car. That morning, I was really confused about where I was. But all the other nights, I had a really good sleep, and was very well oriented, I would say.”

TEAM PLAYERS

If their attitude to sleep makes Zotter’s team sound like hard task masters, then this is a misnomer. He handpicked his 11 crew members, comprised of doctors, physios, and even two photographers, and tested them on a team building day. If assembling a group of motivated individuals with complementary skills was not difficult enough, his task was complicated by the small matter of having no money to pay them. They would be professional only in their ethics and standards.

“Nine months before the race, we had the first team meetings; just to come together, just to know each other, and to talk about what to expect from the race," Zotter recalls. "We had a team building day with a guy who did some outdoor training with us. I think all together it was a pretty good time before the race, but it also needed quite a bit of time from the team members. None of them got any money. They all spent quite a lot of time in race preparation, but also in the race itself.”

Winning the Race Across America would be a labour of love for everyone involved. The payback would be the shared satisfaction of a collective triumph. Zotter says his search for a doctor especially was meticulous, experience having taught him that the medic is often the team member with most to say.